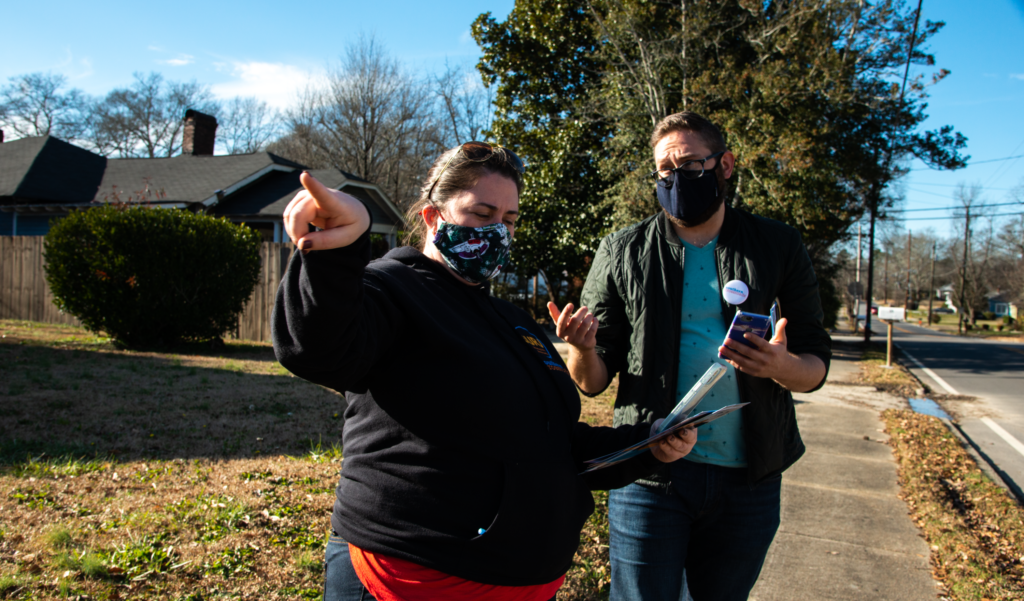

Photo by Sierra King, Survival Media Agency

In “The White Republic and The Struggle for Racial Justice,” published on Organizing Upgrade, Bob Wing contended that the U.S. state is racist to the core, and this has specific implications for our movements’ work going forward, especially the need to replace this racist state with an anti-racist state. Organizing Upgrade is publishing a series of commentaries on this piece, and we invite readers to respond as well. SURJ National Director, Erin Heaney responds in the piece below. Read the response on Organizing Upgrade.

Bob Wing’s piece The White Republic and the Struggle for Racial Justice lays out a critically important diagnosis of the challenge we are up against in this moment: the white republic and the cross-class alliance that holds it together through a strategy of what SURJ (Showing Up for Racial Justice) calls white solidarity. We share Wing’s assessment that the fight for antiracist democracy is the central democratic and class struggle of our time, that the defeat of the white republic is a condition necessary to advance progress on every issue we care about, and that race is the pivot of U.S. politics. As Wing argues, we need a multiracial mass movement to defeat the white republic. This will necessarily require large numbers of white people to defect from white solidarity and instead choose multiracial solidarity.

ORGANIZING TO BREAK THE RIGHT’S BASE

Wing describes this multiracial base: “We need to build the independent strength of the most determined racial, social, climate, and economic justice constituencies – those that understand that inequality, war, and environmental destruction are rooted in capitalism and that the corporate class is an unstable opponent of racism and authoritarianism.”

Part of this work will require organizing a meaningful number of white people into our movement, and we believe our best bet is to organize white communities who have the most to gain from a change in the status quo: poor white people, and especially poor white people in the South.

The white privilege afforded by racial capitalism that Wing describes is of course real, and yet it is not meted out equally. The current system isn’t serving the needs of poor white communities. There were about 65 million poor and low-income white people in the United States before the pandemic. In the South, poverty rates among rural white people are much higher than they are among whites residing in cities, due to declines in jobs such as mining that once provided decent wages. Poor white people who live at or below the poverty level watch their loved ones struggle with hunger, low wages, no access to healthcare, and no access to quality housing because of disinvestment in their communities.

The Right heavily and strategically invests in making sure poor and working-class white people maintain allegiance to white solidarity – the commitment that white people have made to defending white supremacy both consciously and unconsciously, even when this solidarity has negative material consequences in their lives.

Linda Burnham raised this in the lead-up to the 2016 election in an article first posted on Organizing Upgrade in the context of Trump’s rise, but it is just as salient today: “The power of the right cannot be undercut unless a large segment of its base is broken off. Obviously this is a long-term proposition, but whatever tactical moves we and others make in this electoral cycle, we need to retain this lesson into the indefinite future: white rage is lethal to democracy and progress and if we’re not organizing white folks around their suffering, we can be sure that someone else is.”

Organizing poor white people into multiracial formations at scale without falling prey to the class reductionism that ignores race is enormously complex – something no one on the left has cracked yet.

Solidarity between poor whites and people of color has been seen as threatening to those in power since the beginnings of this country. Racial hierarchy was codified after Bacon’s Rebellion, when a wealthy and powerful elite realized that solidarity between enslaved Africans and white (mostly Irish) immigrants threatened the status quo system of its time. Michelle Alexander, Robin D.G. Kelley and others share in depth in the Facing History series about the early stages of the white cross-class solidarity focused on in Wing’s article. Anti-Blackness and white supremacy have been used as a strategy to divide and conquer organized groups of poor and working-class people since colonization and slavery, and have held us all back throughout the history of this country.

There is work needed on many fronts to successfully bring poor white communities into multiracial organizing at scale. But a failure to grapple with the complexity and contradictions of this work isn’t an option right now. The stakes are too high. If we succeed, we make a contribution to building power towards a liberatory agenda. If this organizing is not done, the Right will continue to do it, and poor and working white folks are likely to become the shock troops for fascism in a race war.

While we believe that an approach to ending racism based on saving our humanity as white people is critically important, this alone has not proven to be enough. Yes, we need middle class whites who are part of the current democratic majorities or who have been moved by a desire to end white privilege. But in order to undo and rebuild the state as Wing says, we need more white people joining our movement who will also benefit in deep material ways from these changes.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE SOUTH

We also believe, as Wing has written about in the past, that the U.S. South is a critical geography of struggle and needs to be centered in all of our work. If we are not able to challenge these forces in the South where they are strongest, we will not be able to defeat them nationally. The Right has long known that the key to controlling the country lies in its ability to control the South and, more specifically, its ability to prevent working-class white people from forming powerful alliances with working-class people of color in this region

In March 2015 Wing wrote, “The South is the most polarized center of the fight between the rightwing cross-class white political forces and the multi-racial anti-racist forces. The political crux of the matter is still that white voters in the South vote about 75% Republican compared to the national white vote of about 60% Republican. And Southern Republicans tend to be further to the right than in most other regions. Race and racism are at the heart of the struggle for the South. To sustain their momentum, the far right has implemented a powerful campaign against voting rights and for voter suppression, and racial gerrymandering that must be met by a powerful democratic, antiracist response.”

Unfortunately, many white people on the Left have consistently underestimated the strategic value and importance of the South. This neglect and its consequences are central to a far-right take-over of institutions reflected in the election of Trump and the rise of white supremacist and fascist forces that Wing describes.

LEARNING FROM OUR ORGANIZING WORK

SURJ has been grappling with these complex questions since our founding over a decade ago by many white antiracist Southerners – who had themselves been wrestling with these questions for decades, working in the legacy of SNCC and other Southern movement organizations

SURJ works to develop, implement and hone strategies to break the Right’s hold on a cross-class white solidarity. We welcome and nurture white people who are already realizing that racial capitalism is serving very few. And we organize white communities who are suffering– those who have everything to gain from joining multiracial movements fighting for anti-racist democracy – poor white communities, especially in the South and in rural areas.

Our work stems from a recognition that capitalists have always used race/racism to justify the exploitation of and violence and terror against Black, Indigenous, and other people of color, and to obscure the mutual interest so many millions of white folks have in joining Black-led struggles for structural change. As Wing writes: “…no ruling class can gain the broad social base needed for stability without forming fairly durable but still changing alliances with other social forces.”

Alongside our movement partners and as part of a multiracial, Black-led coalition, SURJ realized the importance of moving white voters to show up as part of the efforts to flip Georgia in the 2020 Presidential and 2021 Senate runoffs. We joined the work led by groups like the New Georgia Project, Black Voters Matter, Working Families Party, Southerners on New Ground and so many others who have been organizing for decades. We hit tens of thousands of doors and made over a million calls to white voters who were likely Democratic, regardless of their voting history. Knowing that the Democratic Party has largely abandoned rural and low income areas of the state, we sought to have in-person conversations with white people in rural Georgia about conditions in their communities and why we thought the elections would help us be able to organize for deeper change. We found white rural and working people hungry to be connected to groups changing the status quo. Many got to that place through the open conversations we had with them.

In the presidential race, Biden made gains in Georgia in majority white counties among whites without college degrees. Our collective work increased the voter turnout of the white Democratic voters who were the least likely to vote by 20%. In the runoff election for Senate, rural voters and white voters with less education turned out at higher rates for the Democrats than they did in the presidential election. Engaging in long-haul organizing in these areas that have been so abandoned is going to be essential to keep this momentum going.

Our organizing project in rural Tennessee is an example of the potential of long-haul organizing. In 2017, working people came together to combat Ku Klux Klan recruitment in their community. Since then, they’ve banded together to knock doors and survey people in the community, and found that access to safe and affordable housing was the issue most widely felt amongst residents. Over the next two years, they won major protections for renters in the region and connected with multiracial efforts across the state and country fighting for housing for all poor people. One of their leaders was recently elected to a city council in a district that Trump won by more than 70%.

If we are able to break up the cross-class alliance held together by whiteness by organizing a subset of poor white people into multiracial coalitions, we undercut a source of the white republic’s power. We share Wing’s assessment that we can only win the types of structural change needed for all communities to survive and thrive by building a cross-class anti-racist united front, led by those most directly impacted by white supremacy and capitalism. Organizing poor and working white people – who are not currently a part of our movement but who have everything to gain by joining multiracial formations, especially in the South – provides a major opportunity to break the power of a white republic.

This article is a collective product drawing on years of work and thought by SURJ members across the country, with some of the writing done by Carla Wallace, Julia Daniels, Evelyn Lynn and Grace Aheron in addition to Erin Heaney.